Abkhaz religious syncretism (I)

By R.M.Bartsyts

Failed to render LaTeX expression — no expression found

A characteristic feature of the Abkhaz autochthonous religion should be considered the presence of stable ideas about the power and characteristics of the life of the soul: “According to the beliefs of the Abkhazians, all living things are the bearer of the soul..., that is, an indefinite supernatural spiritual principle...” Literally translated from Abkhazian, life is that which “contains the soul” ... Before death, the soul “gathers” from the entire body, finally leaves it and death occurs... The body needs the soul everywhere, including in the next world. She should never wander somewhere far from him, and cannot be separated from her body for a long time. Therefore, if a person died in the mountains or drowned in water, and his corpse was transferred and buried in the family cemetery, then it is possible and even necessary to reunite the soul that left the body with this latter. “To do this, Abkhazians perform rituals of “catching the soul” that are unique in their archaic nature... that is, magically collecting the soul in a wineskin at the site of a person’s death and solemnly... transferring it to the grave where the ashes of its bearer rest. This is how the soul unites with the body and moves to the afterlife”.

The presence of these ideas is associated with the cult of ancestors that continues to this day (albeit with a significant transformation in the ritual side), supported by characteristic ideas about the continuation of life in another world, about the inextricable spiritual connection between the dead and their living descendants: “With certain grounds we can say, that almost the entire life of the ancient Abkhaz was serving the souls of the loved ones of the dead. The oath in their name was above all for him; any insult by word or deed to the memory of his ancestors was perceived as a serious crime.”

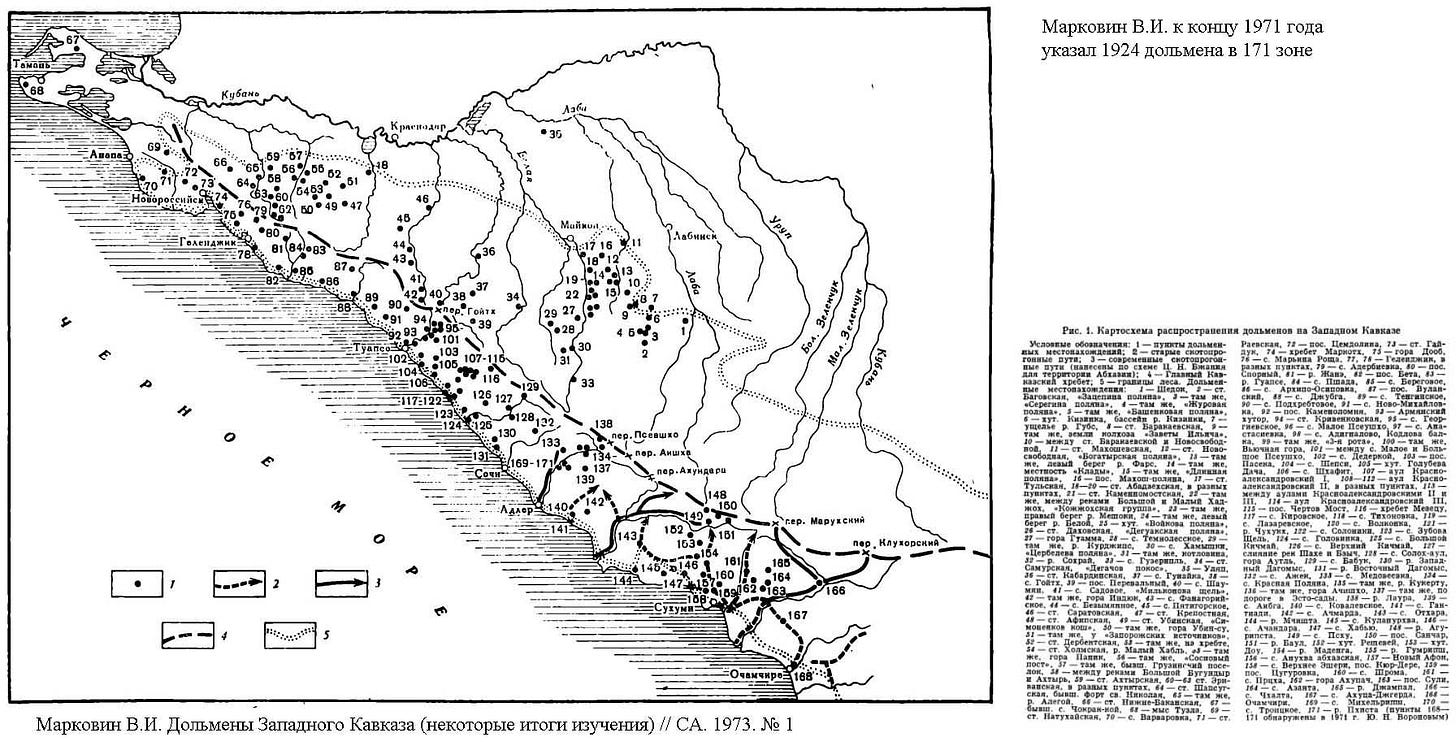

Dolmens deservedly occupy a central place among these religious buildings. As a result of a number of studies, the distribution area of the dolmen culture has significantly expanded; a particularly high concentration of them has been identified in the North-Western (Bzyb) part of Abkhazia. Dolmens are located both in mountain and foothill zones, and in the lower reaches of rivers in Abkhazia. Dolmens are found in the form of single, isolated structures, as well as in small, medium and large groups.

The dolmen culture of Abkhazia, according to research, belongs to the pan-Caucasian megalithic culture, created by closely related ethnic groups that stood at a fairly high level of cultural development. This is evidenced by the complexity of the system of the architectural school, obviously based on a high level of human consciousness. In turn, the skills of using mathematical and geometric data - shapes, size correspondence, choice of special terrain and various architectural techniques developed in practical activities, stimulated the development of culture and spirituality.

It would seem that the purpose of these majestic structures is obvious, however, the literature presents quite diverse points of view on this subject. So, according to various authors, dolmens were used: only for burying the dead; were originally erected with the aim of creating a family sanctuary, only later turning into a burial place; served as permanent or temporary housing. Meanwhile, it is obvious that dolmens are completely unsuitable for housing, even temporary: the holes in the dolmens are so small that an adult, even of a slight build, is unlikely to fit through them. By the way, in connection with this architectural feature of the buildings, from time to time quite bold assumptions appear in the literature that during the burial ceremony in dolmens they used the services of teenagers or dwarfs, who could be found in any ethnic group of any period of social development.

In our opinion, there is no doubt that dolmens were built specifically for the burial of the dead. This is evidenced, first of all, by the Abkhaz name of the structure itself: аԥсдамра “apsdamra” - “house of the dead”. Their original cult meaning is equally clear: the hole in the front slab, intended for transferring the remains of the deceased into the interior, and the cylindrical sleeve covering it have a clear visual resemblance to male and female genitalia. It is logical to assume that this unambiguous allegory of “reverse” sexual intercourse symbolized the rebirth of the soul through the return to the mother’s womb of a person who has completed the cycle of earthly life. Thus, the dolmen builders’ ideas about the duality of the world, the other life, caring for their forefathers, as well as familiarity with such abstractions as “immortality,” “spirit,” “soul,” etc., show a fairly high level of their spiritual development.

Subsequently, probably with the extinction of the cult of rebirth, the dolmen loses its utilitarian functions as a burial place, turning into a purely cult object of worship of the souls of ancestors. According to Y.N.Voronov, “the dolmen group is, apparently, a special family cemetery, which served to a certain extent, judging by the sacrificial platforms and other attributes (bowls, depressions, solar signs, etc.), at the same time for periodic prayers and played the role of a kind of temple complex”

The main evidence of the cult purpose of dolmens are altars, traces of which in the form of a stupa-shaped depression were found in most of the studied monuments. Mentions of the custom of feeding the dead, which is part of the ritual complexes of the cult of ancestors - “apskhu”, i.e. “share of the soul of the deceased” are also present in the legends of the Nart epic. G.F. Chursin emphasizes that “having buried the deceased, the Abkhazians, first of all, take care that the deceased does not starve in the next world.” L.I. Lavrov, exploring the culture of the Shapsugs, a people neighboring and related to the Abkhaz, reported that back in the 19th century they left sacrificial food at the dolmens. Apparently, the ancient Abkhaz, performing rituals associated with the cult of their ancestors, worshiped these tombs, displaying funeral sacrificial gifts at their facades, as their descendants do to this day at fresh graves.

Moreover, in Abkhazia the custom of setting the table of sacrificial food for the recently deceased is still alive: every day until the fortieth day, then every Thursday until the anniversary of death, when a large funeral table is set. This ritual of presenting food to the deceased is called “aishvarglara” - “setting up the table.” It is typical that during its performance, which takes place inside the house, the door must be opened so that the soul of the deceased can pass to the table. It is possible that this custom originates in the era of dolmen construction. In many of the studied structures, the cylindrical bushings that closed the dolmen openings lie nearby, on the site. It is quite possible to assume that during the sacrifice at the entrance, on the front platform of the dolmen, worshipers could specially remove the plug, opening the way for the soul of the deceased, located near the ashes, in the inner room.

It is noteworthy that in this undoubtedly pre-Christian ritual, over time, traces of the influence of Christian rituals appeared: in everyday life, the аишәарглара “aishwarglara” ritual is also called “the formation of a candle.” Indeed, the central place on these memorial tables is occupied by a large candle, which is lit at the very beginning of the meal in honor of the deceased, allowing it to burn out. To celebrate the anniversary, close relatives of the deceased make and “place” a special, large candle - ашьамаҟа “ashjamaka” - woven from many thin and long waxes. It is also allowed to burn out, after which, if a cinder remains, the wax is unraveled and distributed to family members in memory of the deceased.

Scientists involved in dolmen research have identified another characteristic feature of the dolmen burial ritual. The remains of the dead and the accompanying equipment: weapons (arrows, spears, knives, slings), ceramic dishes and individual tools, as well as frequently occurring dog bones, indicate that only men were buried in dolmens. Later, women’s burials were also discovered on the territory of the megalithic complexes, but outside the dolmens, although in close proximity to them. This situation corresponds to the meaning of the cult of ancestors, as a cult of “veneration of deceased male relatives, characteristic of the patriarchal clan system and its later remnants.” The main list of archaeological finds in dolmens consists of copper leaf-shaped knives, copper hooks with a sleeve, small and large copper beads, pins with a hemispherical head, iron objects, and pottery. Due to the mixed state of bones and implements in most dolmens, researchers, as a rule, are not able to accurately determine which bones this or that inventory belonged to. Meanwhile, the presence of a significant number of remains and multi-layered cultural strata in the Abkhazia dolmens testifies to their antiquity and duration of operation.

The archaeological material obtained during excavations objectively indicates that the ancient inhabitants of Abkhazia had a secondary rite of burial, cremation and other characteristic features of the funeral rite. A.N. Malikov examined a remarkable dolmen in Krasnaya Polyana with a single, half-sitting burial, near which there were ornamented clay vessels that were closely similar to the ceramics of the dolmens near the village of Eshera (Sukhum district). There are also other single burials, but with a different burial rite: by cremation instead of corpse deposition. The question of who these majestic tombs were originally built for - leaders and elders or for the entire clan - still remains open. The only thing that matters is the undoubted circumstance that both those and other structures had a sacred meaning, differing, apparently, only in the degree of subsequently acquired “power” and, accordingly, the influence of the cult place. Thus, “the souls of the deceased members of the ancestral family remained under the guardianship of the living and, in turn, had to provide protection to these living ones in all their undertakings. This is the essence of the primitive form of the religion of animism, which gave birth to these amazing monuments at the high stages of its development, i.e. buildings - dolmens, acting as an eternal repository of souls and appearing before us as the main part of the ancient cult of the dead, numerous remnants of which have survived among the Abkhazians to this day"

No less majestic and interesting ancient religious monuments are cromlechs - “monuments of megalithic culture, unique religious buildings that served as temples of the sun.” The architectural features of cromlechs (spiral shape) and materials from archaeological excavations indicate that cromlechs also reflect the developed animistic ideas of the ancient Abkhazians, and the presence of vivid ideas about the afterlife among them. Cromlechs identified on the territory of the republic are localized in Northwestern Abkhazia, in the Gagra, Gudauta and Sukhum regions. They are a complex of concentric stone circles, built from massive stone blocks placed vertically close to each other, with burials with grave goods in the central circle.

All objects found in these structures consist exclusively of ceramics, bronze and a few iron objects; there are also many fragments from various vessels that cannot be restored. Bronze objects include a dagger, arrowheads, pins, a bracelet with two ram heads, lamellar belt yarn, beads and other objects. All burial goods have a direct connection with the objects found in the Abkhazia dolmens. The bones in which these objects were found, as well as in the dolmens, had no anatomical order and were chaotically scattered. During the study of cromlechs near the village of Wathara (Gudauta district) by archaeologist I.I. Tsvinaria found that the space between the circles was densely filled with river pebbles, medium and large in size, which constituted a fairly stable and flat surface, free of grass and weeds. During the archaeological excavations, many interesting finds were made. Particularly notable are a massive stone hammer with a grooved interception, fragments of plates, a miniature hoe made of pebbles, clearly specially made for religious purposes, and numerous tools made of ceramics and pebbles.

Apparently, during the era of the construction of religious megalithic structures in Abkhazia, there already existed a cult of stone, which became widespread in subsequent historical periods and was closely associated with the cult of deceased ancestors. The custom of laying stones on graves is described in a number of tales of the Nart Saga: some informants note that the Narts placed large stones at the feet and at the head of the grave. Archaeological research, including ours, indicates that in Abkhazia the tradition of lining grave pits with stones or stone slabs, lining the surface of the grave with stones or tiles, has existed continuously for centuries. Traces of this tradition are also present in the modern design of graves, which are often framed with three rows of cobblestones, and a certain number of them is used - 60 pieces. In design, such structures, although rectangular, have an obvious resemblance to cromlechs, although their original sacred meaning has been lost.

Within the mound near the village of Wathara, where dolmens and cromlechs are located, six menhirs - lonely vertical stone blocks - were also discovered. The cult purpose associated with the worship of the souls of the dead of all megalithic structures is evidenced by the fact that during their construction the requirements of the rites and rituals necessary in the process of burying the dead were taken into account. In other words, the architecture of these monuments of the ancient culture of Abkhazia reflects the common features of the religious ideas of the Bronze Age. It is worth noting that the location of such a grandiose religious complex is near the village of Wathara, apparently, contributed to the further perception of this territory as a holy place.

According to G.F.Chursin, “… so that the name of the deceased is remembered and blessed, Abkhazians build generally useful structures in memory of deceased relatives: springs or wells for public use, bridges over rivers and streams, gazebos with benches near large roads for travelers to rest, as well as benches for sitting under the shade of trees . All such structures bear the name of the deceased in whose memory they were built.” Obviously, the pre-Christian tradition of building such structures associated with the cult of the dead is very common today. At the site of the regular bus stop near the village of Barmysh (Bzyp Abkhazia), in 1985, representatives of the Bartsyts family built a covered wooden veranda in memory of our tragically deceased sister N. Bartsyts, intended for rest and shelter from the rain for travelers waiting for transport. In 1994, at the turn from the highway to the village of Barmysh, a similar, but more fundamental structure was built by relatives and friends of our young fellow villager D. Makharia, who died in the Patriotic War of the people of Abkhazia in 1992-1993. On this veranda there are not only benches, but also a small table; on the inner wall, the central place is occupied by a memorial plaque made of black granite with a portrait of the deceased young man, dates of life and death, and dedication from loved ones. According to Abkhazian religious beliefs, every traveler who finds temporary shelter at such stops remembers the dead, blessing their memory, thereby making their existence in the afterlife easier.

Monuments of religious worship that have a specific architectural composition include a number of other funeral structures: special wooden platforms on which the dead struck by lightning were laid; ox skins, in which the dead were wrapped, after which the resulting bundle was hung on trees; funeral urns made specifically for burial (Bronze Age jar burials). Jug burials on the territory of Abkhazia have been identified in many places and are well studied. At the same time, the first two types of the above-mentioned structures were used exclusively as an intermediate option in secondary burial rites. Therefore, they have not survived, despite the fact that the ritual of secondary burial, unique in world culture, with hanging a dead person wrapped in skin on a tree (bending its top into the ground, then releasing it with a tightly tied bale), judging by numerous reports from eyewitness travelers, was still used during the late Middle Ages. When the body decayed and “the bones began to rattle” the bale was taken out, and the bones were given a secondary burial in compliance with the proper rituals. The custom of placing those killed by lightning on a platform continued until the twentieth century. It is directly connected with the cult of Afy - the deity of lightning, thunder and war of the traditional Abkhaz pantheon. Death from a blow from Afy was considered very enviable, indicating the chosenness of the deceased. Therefore, according to the Abkhazians, he deserved special honors: around the platform, close relatives and fellow villagers, dressed in white, performed ritual round dances, accompanied by special choral chants. There was a strict ban on crying and any expressions of grief. After complete decomposition of the body, the bones were given a secondary, no less honorable, burial.

In our opinion, the lists of monuments of a cult nature cannot but include such structures as the Atsanguara (ацангәара - atsangʷara), the “Fence of the Atsans”, widely represented on the territory of Abkhazia, the legendary tribe of dwarfs from the tales of the Nart Saga. It is generally accepted in the scientific tradition that these rough stone fences located in the Alpine zone represent pastoral buildings of the Bronze Age, and they were used as cattle pens until the 19th century.

Meanwhile, based on the presence of external stone circles around the structures, coinciding with the architectural practice of the cromlechs, and entrances on the eastern side near a number of atsanguara, a number of scientists make fairly reasonable assumptions that these monuments were also temple buildings: “Atsanguara can most likely be equated with to the cromlechs, in any case, the atsanguars are monuments of cult significance.” These authoritative opinions allow us to include consideration of these monuments in our work, although, in our opinion, it is still impossible to say that they were originally built only for the purposes of cult worship. Indeed, it is difficult to explain the need to build such a significant number of religious objects in the mountains, where people traditionally stay only for a short period of time: mainly in the summer, during the period of transhumance.

At the same time, it is noteworthy that in the Atsanguar complexes, in addition to round and oval-shaped stone fences, there are also individual structures of a clearly cultic nature - mounds. Such a mound was recorded during our archaeological research of copper mines in the Bashkapsar tract in 1988. During the expedition, the head of the detachment A.I. Jopua explored a complex of several atsanguars located at the foot of the mountain and surrounded by a common fence. At the entrance to one of the atsanguars, a small artificial hill was discovered. During archaeological excavations, fragments of household ceramics were discovered in it.

Apparently, the mound served to fulfill the custom of constructing temporary graves for people who died in the mountains, which existed until the twentieth century. When returning from a mountain journey, the companions removed the body of the deceased to take it to the valley for proper burial. At the same time, the above-described ritual of “catching the soul” and placing it in a wineskin was performed, followed by transferring it to a permanent grave. The mound was restored, after which this peculiar cenotaph became an object of cult worship.

Apparently, it was these ideas that determined the emergence of the modern tradition of constructing memorial complexes with cenotaphs for those killed whose bodies could not be found. So, on the bridge over the Gumista River, where the front line passed in 1992-1993, such a complex spontaneously arose in memory of the soldiers whose bodies were carried away by its waters.

C. Bzhania, generally criticizing the interpretation of the atsanguara as exclusively cult monuments, admitted that the orientation of the entrance of many atsanguars to the east is due to the religious beliefs of the Abkhazians: “This habit is apparently associated with the cult of the Sun, which occupies not the least place in the rituals associated with the god Aytar." Most likely, atsanguars were originally built for the temporary residence of shepherds and livestock, but some acquired cult significance over time. Let us note that this practice of sacralization of architectural objects was preserved in Abkhazia for many centuries. Thus, over time, medieval defensive structures became sacred places - a fortress in a gorge near the village of Bzypta (Bzyp Abkhazia), a rock fortress near the village of Mchyshta (Bzyp Abkhazia), a fortress near the village of Atara (Abzhywa Abkhazia). Today, the most famous complex of cult significance is atsanguara, located on the top of Mount Napra (Bzyp Abkhazia), inside of which there is an altar with a significant number of offerings. Obviously, the cult meaning of the rituals performed there was the desire to appease the spirits of the mountains, thereby ensuring a safe and successful path through the pass, where one of the oldest trade routes passed. In August 1975, Yu Voronov, S Lakoba and V Levintas, having made a difficult ascent, carried out a detailed study of this atsanguara, which is a rectangular double room. The walls were erected dry, from limestone fragments, decreasing as the walls grow, erected to a height of up to 1.5 m, up to 1 m thick. In terms of layout, the monument does not differ from ordinary atsanguara, but the entire internal space of its main room, with an area of about 6 m2, It turned out to be filled with numerous iron arrowheads, forming a layer more than 40 cm thick. In the continuous pile of these arrowheads, silver medieval coins, iron crosses, carnelian beads, sacrificial clay vessels, animal bones and other things were occasionally found.

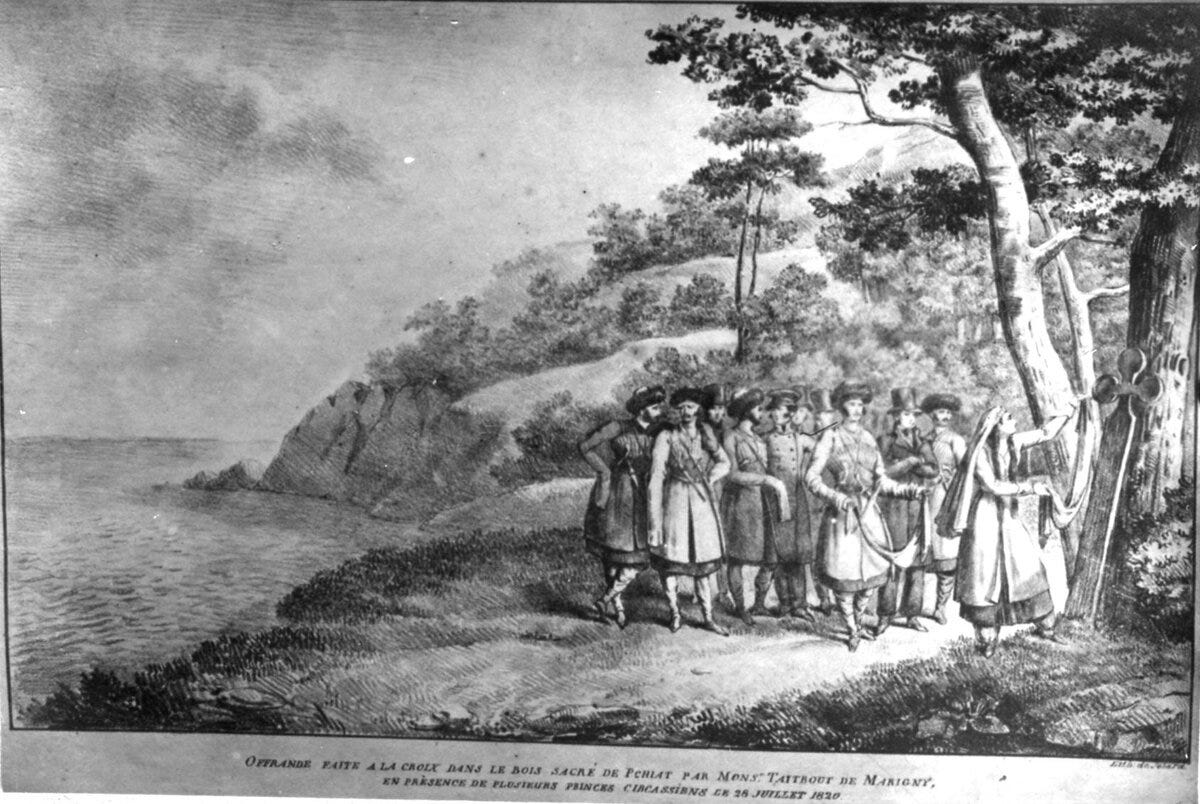

Of particular note is the message that “about a dozen roughly processed iron crosses with rounded extensions on three short ends were found in the altar.” These crosses, the fourth, long end of which was pointed - for attachment to a tree, served as a talisman. This ritual, cases of which are still performed today, consists in the fact that an Abkhaz, if necessary, to leave any valuable property unattended, would strengthen a cross on it - аџьар (adjar). Such a talisman served as a fairly reliable protection against thieves: to encroach on such property was considered blasphemy. The ritual features noticeable features of Abkhazian syncretism: the use of a cross when performing a clearly pre-Christian rite. Moreover, for the rapid production of a talisman - from twigs tied crosswise - it was considered preferable to use the branches of any of the sacred trees: oak, hornbeam, hazelnut, beech, alder, linden etc. The presence in the altar of specially pre-made iron amulets (iron was also considered a sacred material), apparently included in the working equipment of merchants, is additional evidence of the importance of the pass road through Mount Napra as a trade artery.

A similar sacred place dedicated to the spirits of the pass is located on a mountain path near the village of Blabyrkhwa (Bzyp Abkhazia). It is a flat area at the side of the trail. Until the 70s of the 20th century, a huge, 5-6 girth, lonely spruce stood here. Hunters and shepherds stopped at its foot, leaving some of their property - nails, knives - as if as a guarantee of a successful trip: “so that they could pick it up on the way back.” Sh. Inal-ipa, while exploring the atsanguars on the left bank of the upper reaches of the Bzyp River (Bzyp Abkhazia), on the pass of Mount Dzyna, also discovered “on a huge white stone slab a whole pile of arrows, donated at different times by different people to the spirit of the mountains”.

F. Tornau also mentions a similar altar on the pass across the Main Caucasus Range, in Abkhazia, near Mount Kapyshstra: “These altars consist of several stones folded in the form of a quadrangle. Here, everyone crossing the ridge is obliged to put some kind of offering to the Spirit of the mountain, who will send him fog or a snow blizzard on the road. Usually these are bullets, money, some kind of “unnecessary” weapon. Nobody dares to touch these things. These altars obviously belong to ancient times, since on some of them, in the pile of offerings accumulated over centuries, there are, among other things, iron arrowheads and spears, which is where the Abkhaz name for such altars comes from - akhchahyku, that is, the place where the arrows lie»

Paying tribute to the observation of the eyewitness, it is worth noting that, according to custom, travelers were allowed to take anything they urgently needed from the property sacrificed. However, there was a mandatory rule: leave some other thing in return. Of particular interest is the pottery found in many of the altars. If other objects - arrows, crosses, coins, were not originally made for sacrifice, then pottery: fragments of jugs with ornaments, bowls and miniature vessels, were clearly specially made for offering sacrificial food to the spirits of the mountains. Bones of sacrificial animals are often found in altars. Most likely, atsanguara became objects of religious worship during the period when more developed forms of religion associated with the deification of natural objects appeared among the ancient Abkhazians. Thus, on “an animistic basis, the cult of nature began to take shape, personified in the images of all kinds of spirits of the animal and plant world, earthly and heavenly forces... The magical practice of strengthening the power of the sun, enhancing the fertility of the earth, causing rain, etc. began to take shape.”